First, one might expect all of the elements to have been "discovered," since humans did not first "create" such elements such as oxygen or hydrogen. Furthermore, many elements that had been artificially synthesized-- such as Technetium (Tc)-- had been found to be naturally occurring also. So is this area of chemistry actually a simple series of discoveries?

Not quite. (Of course, chemistry would not let us off that easily.) The key phrase in that previous paragraph is the reference to "many [synthesized] elements." In fact, there are elements which we know of solely by synthesis. The most recent example is about Element 117, which was successfully synthesized on 2010.

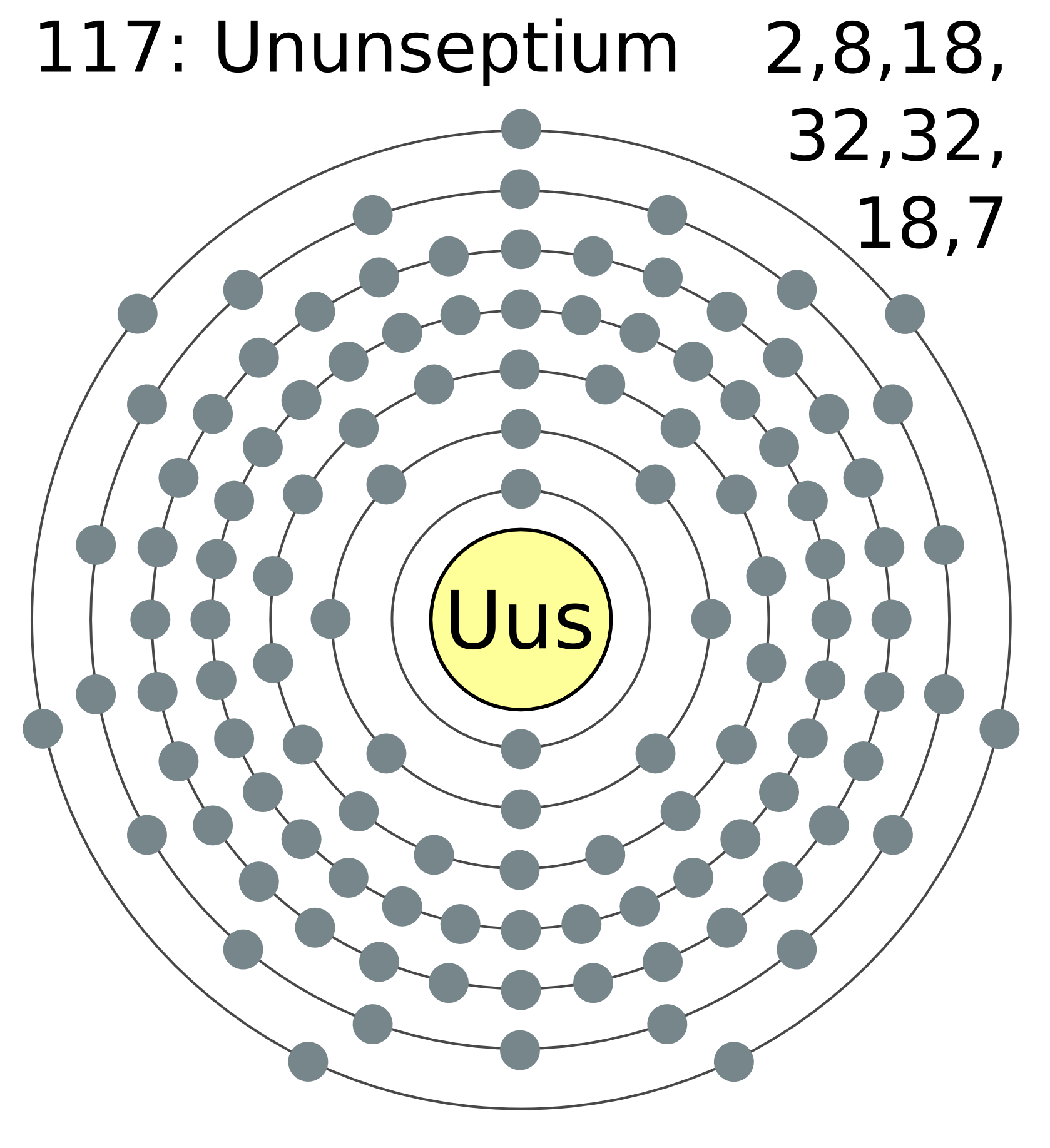

Temporarily named ununseptium (Uus), the element is one of the heaviest element that we know of.

(A Simplified electron cloud model of ununseptium: each dot represents an electron, and each number on the top right corner denotes the number of electrons in each "ring," starting from the inner-most one)

As we defined previously, a discovery involves "unknown" materials. Although some specific details of the element had not been known, at least the general possibility of the concept had been known since the creation of the periodic table. For example, we knew that a theoretical Element 117 would have 117 protons. Moreover, this element had not been "found" like how other elements such as oxygen had been found (for instance, this was not found in a "natural surrounding"). But most importantly, the team that created the element had planned and used specific procedures to form the element that did not exist beforehand. This directly correlates to the definition of "create."

Therefore, we can see that artificially synthesized elements such as Uus are more results of creation than discovery; yet nonetheless other "naturally occurring" elements are results of discovery than creation. It is very perplexing to see that even in the realm of the basic building blocks of chemistry-- the world of elements-- the conflicting distinctions between discovery and creation is evident.

On a last note, Dr. Kenton Moody, a member of the team that created Uus, declared that,

The question we’re trying to answer is, ‘Does the periodic table come to an end, and if so, where does it end?’His question reveals yet another in response, which we will leave as an open question for now: Is there a limit to such achievements of creation, or are we bounded by the things we can discover?

No comments:

Post a Comment